- Home

- Gun Brooke

Soul Unique Page 2

Soul Unique Read online

Page 2

“You were hoping to draw more business your way if I endorsed your art school.” I shook my head. “You show poor judgment on so many levels, and employing people like ‘Maestro’ here is just one such mistake.”

I couldn’t care less what this woman thought of what I said. I did, however, feel a little bad for the poor students who stood there like statues, no doubt seeing their dream careers as painters vaporize before them. “Keep in mind that I’m basing my opinion on what I see on your easels right now. You may have decent artwork displayed elsewhere, but if I were you, I wouldn’t use any of the techniques or advice Mr. Gatti has taught you.”

A young man standing to my far right stepped closer. “Ma’am? Ms. Landon? We do have an exhibit we want to share with you, if you would like to stay for just a moment longer?” He blushed a saturated pink. “We would value your opinion, even if it stings.” Smiling crookedly, he shrugged. He seemed like a nice young man, and I do care about painters, no matter what my reputation states.

“Very well.” I didn’t even glance over to the frantically whispering Gatti and Leyla. “As I did make time to visit you, I might as well.”

The young man looked relieved and motioned for me to walk through the door. “I’m Luke, by the way. Luke Myers.”

“Nice to meet you.” I thought I’d better be on my best behavior, as the students all followed me toward a larger room farther down the corridor. They all kept a certain distance, as if afraid I’d slit their throats if I didn’t like their paintings.

An expert had lit the room to display the art; I had to give the school credit for that. I walked up to the first piece, a watercolor painting of the Statue of Liberty.

“Subject is boring, but whoever painted this knows about light. Use this technique and do landscapes instead.”

“Thank you, ma’am,” a girl’s voice whispered from the back. I didn’t turn around but moved to the second piece. This one was an oil painting of a dark, gritty alley. “Shift focus. Less on the yellow tones, more on the blues. Good brush technique. Good depth.”

“Wow.” A young man high-fived another.

I walked from painting to painting, critiquing and making sure I had at least one positive thing to say about each of them. It wasn’t these kids’ fault they had an idiot for a teacher and a complete fool for a principal.

“Did you get it, Luke? Did she let you put it up?” a young woman to my left whispered.

“Yeah, it’s right behind this wall. Out of sight of Rowe.”

My curiosity rose as I turned the corner. I walked up to a canvas much bigger than the others. And stared. I stepped back to get a better overview but was unable to keep my distance for very long. I walked closer again. The colors were close to blinding in their clarity. A child stood by a window, hands pressed against the glass, and my throat clenched at the immense loneliness the painting portrayed. The glass seemed like it might shatter beneath the little girl’s hands, and the curtains framing it were of the thickest, richest velvet. The dark hair of the girl glimmered in the muted light coming from behind.

“Who—” I cleared my voice. “Who painted this?” I rounded on them, scanning the young faces. Nothing of what I had seen so far was even close to this. “Who?” I asked for the third time, my voice husky.

Luke took a step toward me. “Hayden. Hayden Rowe.”

Chapter Two

I blinked as I regarded the painting in silence. Hayden Rowe, the rude girl that had made Gatti almost levitate from frustration. Leyla Rowe’s…daughter?

“And what, pray tell, is a piece of this caliber doing here, grouped with those of students who have a lot left to learn?” I turned to Luke, the unofficial spokesperson of this group.

“I’m in my third semester here,” Luke said. “During that time, I’ve managed to catch glimpses of Hayden’s work on quite a few occasions. She’s an amazing painter, but our principal, her mother, doesn’t want anyone to see any of her work.”

“That doesn’t make the least bit of sense.” I placed my hands on my hips and examined the painting of the little girl from all angles. “If the rest of her pieces are as good as this one, why haven’t I ever heard of this young woman?”

“Because her mother keeps her locked in the attic.” One of the girls, Goth inspired, black-haired, and with tons of smudged black eye makeup, spoke with disdain. “You saw her earlier.”

“Ulli, please. Nobody has locked up Hayden.” Luke shook his head. “Though, since Gatti started teaching here, who knows? He’s the one who always talks about keys and guardians.”

“That’s because Hayden doesn’t buy his credentials.” Ulli stood her ground. “Personally, I think Hayden scares the shit out of that little weasel.”

As much as I agreed with this Ulli’s assessment of Gatti, I wasn’t prepared to let these young people digress. I was standing in front of something unimaginably good, and if this Hayden had more like this, I wanted her work in my Manhattan gallery.

“How can I get in touch with Hayden Rowe?” I turned to Luke, who seemed to be the one with his head screwed on right. “Anyone have her card or her cell number?”

“Good luck with that, Ms. Landon.” Another of the students, one of the gangly young men, snorted. “I doubt if Hayden bothers with either.”

Granted, business cards weren’t every painter’s thing, but who in today’s world didn’t have a cell phone? “All right,” I said slowly. “Where does she work? Where does she live?”

“In the south wing. She has her studio there, I think. At least that’s what one of the janitors said.” Luke frowned. “I’ve never been there. None of us have.”

“I heard she used to live in this posh place right on Beacon Hill before, but she had to move here about a year ago. Not sure why.” Ulli pulled half her gum out, twirled it around a paint-stained finger, and put it back in her mouth.

“Then point me in the right direction,” I said, set on following this situation up right away, preferably before Leyla and Gatti realized what I was up to and threw me out. “I still don’t understand why Leyla Rowe doesn’t capitalize on her daughter’s talent when that would attract all the attention she wants for her school.” I gazed at the students, who managed to look ill at ease, all of them at the same time.

“Our principal is not advertising Hayden’s talent because her daughter is retarded.” Ulli shrugged. “That or insane, depending on which day of the week the subject comes up.” Flinging her hands in the air, Ulli made a face at her classmates. “Hey, I’m not the one saying this about Hayden. Her mother is, when yelling at her son.”

So Leyla and her son were arguing about Hayden. Perhaps the son felt bad for how his mother treated his sister? The scenario was intriguing no matter what.

“Thank you for showing me this exhibition of yours,” I said to Luke and the others, handing each of them my card. “In my opinion you showed more hospitality and decorum than I’ve seen from the principal and Gatti. Don’t hesitate to stay in touch. Each of you has talent, but you need to develop it with other teachers to guide you rather than Frederick Gatti.”

“Thank you, Ms. Landon.” Luke smiled, and even Ulli looked pleased at what I had to say.

“Greer. Please. Now, can anyone of you show me the entrance to the south wing?”

“Sure. We’re off to have our lunch break. We pass the south wing on our way to the cafeteria.” Another of the girls, petite and with chalk-white blond hair, took a step toward me. “And I do have a business card, Ms.—Greer.” She smiled shyly and handed over a very artsy-looking card. “Never too soon to start, I think.”

“Now that’s what I’m talking about.” I tucked her card away as we all walked out of the gallery.

The students guided me through a maze of corridors, and just as I could smell that we were nearing the cafeteria, they came to a halt next to a large oak door. “Here’s the south wing. Don’t be surprised if she doesn’t open up.”

“All right. Thank you.” I watched them

disappear in the direction of the smell of coffee and French fries. Regarding the door with a sudden, and for me unusual, bout of trepidation, I lifted my hand and knocked.

How anticlimactic it was when nobody opened. I tried twice more, and then I moaned out loud when Leyla’s voice announced her approach, accompanied by the clacking of her high heels. Thinking fast, and yes, I realize, about to trespass, I tried the door handle. To my surprise and relief, the door opened. I stepped inside and closed it behind me, praying Leyla wouldn’t have the same goal as I did. She was talking to someone, perhaps Gatti, so maybe they were on their way to have lunch and bitch about me. I was sure they had plenty to talk about regarding my rudeness in particular and what a horrible person I was in general.

I looked around the hallway, which was devoid of furniture, or mirrors for that matter. Glancing into the rooms, I saw they were all unoccupied and very sparsely furnished as well. At the far end, a winding, narrow staircase led up to the next level. I figured that since I’d come this far, it’d be ridiculous not to continue. Even if Hayden Rowe wasn’t there, I might find more paintings by her.

The metal staircase led me up to an amazing room. Enormous windows let in all the light a painter could dream of. All different sizes of canvases lined the walls, facing away from any visitor. At the far end, long shelves held jars of brushes and wooden boxes of what I surmised were oils, acrylics, and watercolors. Four empty easels sat to my right, and in the center of the room, an occupied easel covered with a tarp sat, making my fingers itch.

“Why are you here?” a now-familiar alto voice said from behind me.

I turned around and finally got a good look at Hayden Rowe. Her shoulder-length dark hair wasn’t just brown. It had a multitude of shades of gold and chocolate and even some copper highlights. I suspected they were all natural. Her eyes were dark, dark gray. The curvy, full lips I remembered from earlier looked impossibly soft.

Her stance was watchful, but not intimidated or nervous. I realized she was waiting for me to answer.

“Hello, Hayden. I saw one of your paintings in the gallery. I find it amazing.”

“Why?” Hayden asked, sounding curious.

“Because it spoke to me. It filled me with emotions, and I wanted to learn more about the child in the painting.”

“You claim that my painting had a voice?” Frowning, Hayden tilted her head. “I don’t understand what you mean.”

“The way you paint, the way you express yourself in your painting, makes me think of my own childhood.” I don’t know how I realized I had better keep my reasoning clear and simple. “I really liked it, Hayden. It’s a good painting.”

“Okay.” She looked less confused. “You’re Greer Landon.”

“Yes, I am. Have you heard of me?”

“My mother has often talked about you. She wants you to come and visit the school. Good for business.” She did a good impersonation of her mother with her last words, using Leyla’s inflection and voice.

“I’m pretty sure I disappointed your mother today,” I said, wanting to be honest with this unusual young woman. “I was almost on my way home when Luke and the others showed me the gallery. They had hung your painting of the little girl there as well.”

“Without telling Mother.” Hayden shrugged. “Probably Luke.”

“He seems nice.”

“He acts friendly.”

Acts friendly? I tried to wrap my brain around what Hayden was saying. “He acts friendly”? That wasn’t the same as saying that someone was a friend.

“May I see some of your other paintings, Hayden?” I thought we better get back on track.

“Sure.” She seemed to hesitate. “Unless you plan to tell Mother. I don’t like it when she screams.”

“I won’t tell a soul.”

“As long as you don’t tell Mother’s soul.”

I smiled at that, but she met my eyes with a serious, steady glance. “I promise not to involve your mother.”

That reassurance relaxed her and she motioned toward the far wall of the studio. “Over there is my most recent work.”

I swear my hands tingled as I strode over to the canvases. Choosing a square, rather large one, about forty inches across, I placed it on one of the empty easels and took a few steps back. And lost my breath. I had to cover my trembling lips with my hand, which shook too, as I took in the motif. Here, a long, winding picket fence started from the left and went across a field next to a gravel road. On the other side of the fence, the grass was emerald green, the trees lush in the golden sunlight. In the distance I saw a glittering sea. Then on the inside of the fence, the grass was dead, and moss and dirt covered the stones. The trees were bare, and in the center on the ground lay a doll with its hair chopped off, dressed in worn clothes, and missing an arm.

I put the painting back and grabbed another one, this one a little smaller, around thirty by forty inches. Again I placed it on an easel. Before I studied it I turned to see what Hayden was doing and found her immersed in her work over by what had to be her latest canvas.

I took another breath and turned to study the second painting. This time, unexpected for some reason, it was a portrait of an older woman. Her short, white hair framed a beautiful face where each wrinkle only seemed to add to her beauty. Dark-gray eyes, looking familiar, reflected the smile on her lips. Clearly, this woman meant something special to Hayden.

“Who is this?” I asked, too curious to even consider if my question was appropriate.

“My grandmother. Isabella Rowe.”

“I like how you painted her.” Unsure if I should say more than that, as Hayden didn’t seem interested in any detailed critique, unlike the young people downstairs, I kept rummaging through the canvases.

I looked at three more paintings, and each of them described a wealth of emotion with unbelievable range. After viewing those six paintings, including the one in the gallery, I was drained, having gone from laughter to tears and from there over to some sort of fear and even anger. I couldn’t remember feeling like this and getting so lost and wrapped up in a painting in a long time.

I made sure I placed the paintings back just as they were. For some reason that seemed important. I turned and walked toward Hayden, who was painting and not even looking at me. I made sure I stood on the other side of her canvas, as I had learned many years ago just how sensitive some painters were about anyone watching their unfinished work.

“Don’t you want to see this one?” Hayden motioned toward the canvas.

“Sure. If it’s all right?”

“It is.” She stepped to the side a little as if to give me room.

I rounded the easel and scanned the canvas, almost bracing myself. This motif was dark. And I felt my eyes widen, as I’d been to this place. A long corridor stretched into the distance, longer than in real life, but the mirrors were the same heavy, gothic gold-framed ones I’d just left downstairs. Here in the painting, each mirror showed a face. I recognized Leyla, Gatti, and some of the students. Other faces were unknown to me, but their expressions went from contemptuous and angry to friendly and even pitying.

“Oh, Hayden. It’s remarkable.”

“So you like this one?” Hayden sounded matter-of-fact, but her hands squeezed the brushes so tight, her knuckles were pasty white.

“I’m not sure ‘like’ is the right word.” I kept my gaze on her, trying to judge if she understood what I meant. “This painting brings out so many feelings in me. Anger. At your mother, to be honest. Contempt, toward Gatti. Fear of the person over there.” I indicated a woman farther away in the painting. “The boy over there makes me want to chuckle.” I pointed at a child in his early adolescence. “So you see, ‘like’ is not adequate.”

Her stance relaxed. “My mother says you’re the expert everyone else listens to when it comes to art. That’s why she wants you to endorse her school.”

“I realize that. Yes, I hold a certain position in the art world. This is true.”

&nbs

p; “Are you going to?”

“Endorse the school? I don’t know. It depends on who’s on the faculty. Gatti’s got to go. If he stays on, I won’t touch this school with a ten-foot pole.”

Hayden frowned, and even if she didn’t say anything, I somehow grasped that I’d used too much imagery in my explanation. “I won’t endorse it if your mother keeps Gatti on the faculty. You said it yourself. After he started teaching, the students stagnated.”

“Yes. He isn’t a good teacher. His paintings are pretentious and don’t depict what he claims they do.”

“An astute observation.” I gazed around the studio. At the other end of it, opposite where Hayden kept the canvases, I spotted a cot and several half-open suitcases. “You spend the night here often?”

“I spend every night here.”

“What? You live here?” Shocked, I stared at her.

“No. I spend my days and nights here.”

Sure, who in their right mind would call it living? It was brilliant as a studio but hardly homey. “Literally living out of your suitcases?”

“My clothes are in my suitcases. I sleep on the bed.” Frowning, Hayden crossed her arms.

“Yes, of course. May I ask why?”

“My grandmother broke her hip and suffered a stroke.”

I thought fast. “And you used to live with her?”

“Yes.” Hayden looked quite relieved.

Guessing it would be a mistake to push her on further details, I was about to ask her if I could show some of her paintings at my Manhattan gallery when a furious voice interrupted me.

“What the hell are you doing here? Do I need to call the police and have them escort you from my school?” Leyla stood in the middle of the floor, her eyes narrowing into slits of fury. Gone was the pink-princess-cake persona from earlier.

“This is my room, Mother. Call the police if you like, but Greer can stay if she wants.” Hayden stepped in between her mother and me.

Lunar Eclipse

Lunar Eclipse Piece of Cake: The Wedding

Piece of Cake: The Wedding Speed Demons

Speed Demons The Blush Factor

The Blush Factor Insult to Injury

Insult to Injury Change Horizons: Three Novellas

Change Horizons: Three Novellas Warrior's Valor

Warrior's Valor Escape

Escape Rebel's Quest

Rebel's Quest Thorns of the Past

Thorns of the Past September Canvas

September Canvas Pathfinder

Pathfinder Soul Unique

Soul Unique A Reluctant Enterprise

A Reluctant Enterprise Advance

Advance Pirate's Fortune

Pirate's Fortune Protector of the Realm

Protector of the Realm Sheridan's Fate

Sheridan's Fate Wayworn Lovers

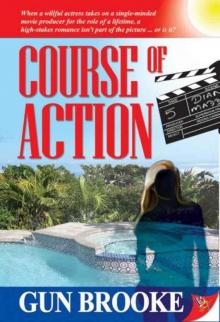

Wayworn Lovers Course of Action

Course of Action