- Home

- Gun Brooke

Insult to Injury Page 4

Insult to Injury Read online

Page 4

When she finally gets up and moves to another part of the house, I sigh in relief. I haven’t been close to anyone since I was four, and though I’ve overheard enough anxiety, grief, and sorrow in the shelters and under overpasses, nobody else’s tears have impacted me like this before.

Shaking myself like dogs do, literally, as it loosens me up, I check the time on the wall clock that shows the East Coast time, Pacific time, and Greenwich Mean Time, for some reason. It’s hooked up to the solar-panel wiring and works perfectly still. Six p.m. It’s getting dark outside, and I need to sneak out and head to Westport. I saw a note about an open mic evening at a restaurant. It might earn me some cash and save me from having to live on fruit preserves alone.

I dress in the only decent clothes I own—black jeans with tears that look intentional, a black T-shirt with a sequined butterfly on the front. My sneakers and my army surplus jacket will have to do. I have nothing else. I regard my reflection in the bathroom mirror. My hair is okay—a little unruly in a way that can also seem like I meant for it to look like that. I have a very short stump of a kohl pen—it’s one of my five sample-size pieces of makeup—and I use it sparingly around my eyes. I use everything sparingly. It’s simply my way of living.

After listening carefully for a few minutes, I slowly push the shelf open toward the basement. It makes a bit of a noise, but not too bad. Closing it again, I make sure it’s aligned with the rest of the shelf before I walk to the door leading out toward the garden. Not a soul in sight. Perhaps Gail has gone to lie down after being sad. I’m not sure how I figure this, but she doesn’t strike me as a person who allows herself some tears very often. Life would be quite exhausting for her if that’s the case.

I hurry into the bushes and disappear behind the shrubbery. If Gail has this part of the garden trimmed, I’ll be in trouble. That or I’ll have to do an army-crawl on my belly to the house. Yay.

The walk into Westport is rather pretty, during the daytime. Now the sun has just set, and dusk is coming. I can see fine where I walk; it’s not that. It’s more the long shadows cast by the trees and bushes along the way, created by the very last, faint sun rays, that spook me. I was often afraid of the dark as a kid but never dared to mention it to Aunt Clara. Sure, I tried a few times when I little, but the scornful huff at how bad such imaginings were didn’t exactly encourage me to confide in her about it. It’s odd that I’m feeling so secure in the basement even if there’s no natural light, and if the solar panels go bye-bye, I’ll be staying in a tomb. Perhaps I should try to stock up on some of those cheap batteries for LED flashlights you can get at the dollar store with the money I might make at the open mic. The owners of the restaurant won’t pay anything, but some patrons might give tips if they like what they hear.

I’m relieved when I see the faint lights of the first houses on the outskirts of Westport. Energized, I lengthen my stride, and soon I feel the sidewalk under my feet, rather than the asphalt road where cars pass pedestrians way too close. They really should extend their bicycle paths around here.

It isn’t hard to locate the restaurant, as quite the crowd is heading that way. Damn it. I hope they haven’t filled all the slots. I may have made a huge mistake thinking that a small town like Westport wouldn’t have too many hopefuls when it came to these kinds of events. I’m standing in line to enter when I realize that another line is forming more slowly next to me.

“What are you doing? Standup comedy again?” a young man asks the boy next to him, grinning.

“I have some new jokes that Dad says need a bigger audience,” the boy, perhaps twelve, says, sounding precautious and, of course, adorable.

“I’m rapping one of the songs from Hamilton,” the young man who started the conversation says.

“Cool!” High-fiving the older boy, the standup comedian whoops.

The penny drops for me. “Excuse me,” I say, turning to the boys. “Is that line for the performers?”

“Sure is,” the youngest says. “You entering?”

“I am.” I take a step closer and place myself behind them just as two teenaged girls run up. They don’t seem to mind but smile and nod.

“Like your hair,” the tallest of them says.

“Thank you,” I say, dumbfounded. “Your outfits are cool too.” They’re both dressed in long blue cloaks over black jeans and T-shirts.

“It’s our choir outfit.” The shorter girl twirls. “Fancy, huh?” She giggles.

“I think so.” I smile faintly. It’s apparently not hard to be charmed by the kids in this town.

“Haven’t seen you around,” the taller says, tilting her head. “Then again, I live just outside East Quay. I’m Stephanie, by the way. Stephanie Edwards-Bonnaire.”

Also fancy. “I’m Romi.”

“Singing?” the other girl asks. “My name’s Lisa.”

“Yes.” I’m starting to get nervous with all this friendliness. In my experience, people are never this up front and happy-go-lucky unless they’re trying to put one over on you. Still, I can’t be deliberately impolite. If nothing else, that would attract too much attention to me as a person. “Nice to meet both of you.”

“My moms are coming tonight to listen to us. Usually it’s just Tierney, but as Giselle’s, that’s my other mom, well, her dog is back from the vet, so she can come for once. I hope they reserved the table over by the emergency exit for her.” Frowning, Stephanie, whose explanation fails to make much sense to me, looks concerned.

Lisa nudges Stephanie. “Hey, you checked twice already.”

“Yeah, you’re right.” Stephanie must notice that I look confused. “Giselle has agoraphobia and needs her service dog to manage. She’s come so far this last year.” Pride in her mother’s achievement makes her beam. So, she has two moms. Awesome. I tell myself I’m not envious, but of course I would give my right hand for just one, which is ridiculous, as I’m an adult and need to focus on supporting myself—and staying out of prison.

“That’s amazing,” I murmur as the line begins to move. This prevents deeper conversation, and soon we’re in one of the back rooms in the office area next to the kitchen, where the choir turns out to consist of ten girls between ages twelve and eighteen, from what I can see. The two boys I spoke to earlier are there, and a few other people, mainly adults. A waitress takes down our names and what we’ll be performing.

“Stephanie!” A woman moves lithely between the people in the room, her long, auburn hair moving around her like falling autumn leaves.

“Hi, Tierney,” Stephanie says, and then her smile dies on her lips. “What’s up? Is it Giselle?”

“What? No. No!” Tierney stops next to her much-taller daughter. She gazes at each one of the choir members. “However, there’s a small hiccup. Carrie can’t make it. Can you sing without a leader?”

“Not again,” some of the members moan. “She’s barely around anymore.”

“I’m sorry.” Tierney wraps her arm around Stephanie’s waist and another one around Lisa. “I’ll talk to Manon about it. The Belmont Foundation needs to figure this out.”

“We can manage for tonight,” Stephanie says and juts her chin out. “Half the choir couldn’t make it anyway, so we’ll wing it. We’re singing your song ‘Fade Away.’”

Tierney beams. “Aw, you guys.” She kisses Stephanie’s cheek, and the pride she exudes makes my heart ache. Never, not once, have I had someone look at me with such guileless affection. And, did Stephanie say that it was Tierney’s song? Like, she wrote it? Or is it merely her favorite song?

“I’m going back to the table now. Break a leg.” Tierney waves to the other members as she leaves.

I walk over to a corner and try to calm my nerves. In the subway, I’m never nervous, but at open-mic nights, I can get stage fright. Not sure if it’s because it’s a more professional setting and that a lot of people are there to be entertained on a whole different level. In the subway, people can choose to tune you out and ignore you—but this is�

��yeah, different.

The choir is up just before me, according to the list one of the waitresses keeps of us. The young comedian is the last one to perform. I don’t listen to the other performers at these events, normally, but this time, I’m curious about the choir. When they line up on the small stage, they look so happy, I clench my hands.

Memories of trying out for the glee club as a junior in high school takes a jagged path through my mind. I got in, and some of the other kids even praised me, only to have Aunt Clara shoot down my accomplishment when I told her. I had been so certain she’d finally be proud of me. But no. Frivolous activities wouldn’t get me a decent job once I graduated high school. Whenever I mentioned college as a good way of reaching that goal, she dismissed that possibility too. According to Aunt Clara, college was not required to work the till in a store. I remained in the glee club, defiant and upset, and managed to do so until the day I couldn’t take it anymore and left East Quay.

Now the girls sing a stunning rendition of “Fade Away,” which I feel stupid for not recognizing as one of the biggest hits of the summer. I can tell the girls are a little uncertain as they change key, but they hold their own, even without a conductor. If they’re this good without one, they must really shine when their leader is present.

“Your turn, Romi, was it?” The waitress taps me on the shoulder. I flinch and see the stage is empty. “Do you have any sheet music for the accompanist?” She nods to the man at the piano.

“No. I mean, I sing a cappella.” I rub my palms against my thighs.

“All right. On you go.” The waitress gives me a quick smile.

The room is lit only by the small lanterns sitting on each table. I can’t make out anybody but the faces of the patrons closest to the stage, and that’s a good thing. I can just sing and pretend I’m in the subway as usual.

“Hi. My name is Romi and I’m going to sing ‘Never Enough’ from The Greatest Showman.” Musical numbers usually do well, and this song means a lot to me. I haven’t seen the movie, but after listening to the recording at the library in New York many times, I know it well. I never dwell on why, exactly, a certain song speaks to me. It just does.

I grip the microphone hard but leave it in its stand while inhaling deeply. As I start to sing, I know it’s going to be an all-right performance. I don’t add any of the interaction that’s necessary sometimes in the subway. That’d be awkward among this crowd. As I let the song build, I’m grateful for the excellent sound system. Reaching the crescendo and then the soft ending of the song, I can only hope that I’m not the only lover of musicals in Westport today.

There’s a moment of silence, and then the members of the audience applaud and shout in appreciation. Stunned, I stand there, suddenly at a loss how to get down from the stage. Hell. I don’t even know how to let go of the microphone. Eventually, the applause dies down and I take a bow, knowing how important it is to be polite. If anyone here is about to hand me some cash, I can’t come off as an asshole.

The boy with the standup comedy act does well, and people shout his name. No doubt he’s locally known. In a town this size, most people are, probably.

“Romi!” Stephanie and Lisa show up at my side. “You were amazing! You can sing!”

“Thank you.” I have to smile at the exuberant teenagers. “Your choir did a great job, and when you consider the fact you had no conductor, it was even better.”

“You think so? We almost had a disaster at the key change. I hope Giselle didn’t faint. She’s extremely sensitive to such things.” Stephanie crinkles her nose, but her eyes show no real concern. “If anyone sounds pitchy, I swear she breaks into hives.”

“So true. Why don’t you and your new friend come sit at the table? We’ve ordered calamari for the entire table and have seats to spare.” Appearing as if out of nowhere, Tierney shows up next to us. “And I can promise you that neither the choir nor you, Ms…?”

“Just Romi.” I place my twitchy hands on my back, holding on tight.

“Romi. You were a welcome surprise. Won’t you join us?” Tierney regards me with friendly curiosity. “And neither of you was pitchy enough to cause my wife a bout of the hives.”

A free meal? Is she kidding? “Thank you. I’d love to…um…?” What was her last name? Something hyphenated?

“Just Tierney will do, Romi.” Tierney grins. “I see the other choir members are joining their families. Come along.”

I obediently walk behind the other three as we make our way to the table by the emergency exit. It’s a large, round table, able to seat eight people. Four of the seats are taken already.

“Romi, let me introduce you really quick.” Tierney motions to the blond woman that has a black retriever sitting close to her. “This is my wife, Giselle. And that’s Charley.” She points at the dog. “You can pat her if Giselle says it’s okay. Giselle, this is Romi.”

“It’s okay,” Giselle says, raising an eyebrow at Tierney as she extends her hand to me. Her sonorous voice, combined with her classic beauty, makes my mouth go dry, but I take her hand. In a way she reminds me of Gail.

“Nice to meet you, Giselle.” I have an odd feeling that she’s someone familiar, but that’s of course impossible.

“Okay. This lovely lady is Manon Belmont. You may have heard of the Belmont Foundation,” Tierney says and smiles at the woman on Giselle’s other side. With chocolate-brown hair and even, slate-gray eyes, she seems…untouchable, somehow. Still, there’s nothing standoffish about her. Manon just looks like she constantly assesses her surroundings, including its people.

“Hello, Romi.” Manon shakes my hand before indicating the woman next to her. “This is Eryn, my wife.”

I’m greeted by a vigorous handshake as Eryn leans over the table, her long, red braid dangling dangerously close to the large plate of calamari.

“Have a seat, please, and tell us about yourself.” Tierney motioned for the chair between Lisa and Eryn. “We’re always curious about new faces—especially when said face can sing.” She winks at me, but my panic is rising from a level three to at least a seven.

“Nothing much to tell. I’m new around here, staying in the rural area of East Quay,” I say, hoping I sound casual enough. “I saw a poster about the open mic here. That’s about it.”

Stephanie leans past Lisa. “Nah-uh. You sing like a pro. There must be more to your story.”

“Stephanie.” Giselle’s tone is light, but it holds a soft warning. “Let Romi decide what she wants to share.”

“Sure. Absolutely.” Stephanie doesn’t appear to mind the discreet correction. “I just think you’re amazing, Romi.”

“Thank you.” I look longingly at the plate and have to push my hands in between my thighs to not grab a fork and shuffle all that deep-fried goodness into my mouth.

“Why don’t we dig in before it gets cold?” Manon says, and I wonder if she’s read my mind.

“Yay! Calamari,” Lisa says. “Haven’t had Italian since the last time I was here. Corazon makes the best Mexican food, but variety is good, right?” She elbows me gently. Lisa is short, a little chubby, and very cute with her black ringlets falling down her back.

“Who is Corazon?” I ask as I force myself to take just one piece of the calamari at a time, dip it in my own little bowl of dressing, and chew it with so much gratitude I could cry.

“My foster mom. She’s awesome.” Lisa grins and spears a new piece from the large plate.

“Sounds fantastic.” I swallow hard. It does. I’ve never been in the system, and for a long time I was told I needed to be grateful that I had a relative willing to care for me. Seeing Lisa beam as she talks about her foster mom reinforces the feeling I had growing up. Foster care might have been better. Perhaps.

The conversation decreases a little as we all eat. The waiter shows up next to Tierney. “Will there be seven for the main course, Ms. Edwards-Bonnaire?”

“Geez, Phil. Don’t go all nuts with the surnames. We come here all t

he time, and we’ve told you every time that you should use our first names. It’s confusing when we’re sharing last names left and right.”

“Very well. Tierney,” Phil says, looking pained at the clearly frivolous suggestion.

“And yes. There will be seven of us. May we have the menus back?”

Phil has clearly anticipated the request and hands them over to us. My eyes roam the many choices of Italian food. If you’re treated to a meal, nothing’s better than Italian. It fills you up, and the feeling of being full can last almost twenty-four hours. Not tonight, though. These women seem really observant, and if I eat as if I haven’t seen real food in weeks, which is kind of true, they’ll get suspicious. At least that’s what my panic-infused mind tells me.

“Now, Romi, choose whatever you like. No silliness about going for the cheapest alternative.” As if knowing more than she should, Eryn winks at me over her menu. “I know that’s what I used to do when Manon first started taking me out on dates. We used to go to fancy places, and I couldn’t afford to split the check—so I’d order a salad or an appetizer. Don’t even think about that now.”

I blush. I can feel the heat in my cheeks, and I honestly contemplate slipping off the chair and hiding under the table. “Thank you,” I murmur, not knowing where to look.

“Eryn is a bit too straightforward sometimes,” Manon says calmly, “but she’s right. I can understand being invited to have dinner can feel awkward when it’s out of the blue. Trust me, we do this all the time with different choir members and others. It’s no big deal.”

All right. Since they insist. I look up the dish that seems most plentiful rather than expensive or fancy, and it turns out to be a huge pasta dish. My stomach will no doubt rebel tonight or tomorrow, but I can’t resist it.

I eat in silence, listening absentmindedly to the conversation among the other women and girls. Then there’s a lull, no, a dead quiet, and I realize six pairs of eyes are looking at me expectantly. Seven, counting Charley the dog.

Lunar Eclipse

Lunar Eclipse Piece of Cake: The Wedding

Piece of Cake: The Wedding Speed Demons

Speed Demons The Blush Factor

The Blush Factor Insult to Injury

Insult to Injury Change Horizons: Three Novellas

Change Horizons: Three Novellas Warrior's Valor

Warrior's Valor Escape

Escape Rebel's Quest

Rebel's Quest Thorns of the Past

Thorns of the Past September Canvas

September Canvas Pathfinder

Pathfinder Soul Unique

Soul Unique A Reluctant Enterprise

A Reluctant Enterprise Advance

Advance Pirate's Fortune

Pirate's Fortune Protector of the Realm

Protector of the Realm Sheridan's Fate

Sheridan's Fate Wayworn Lovers

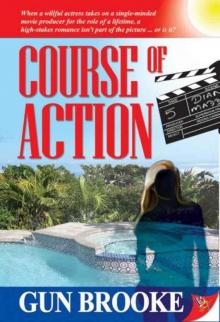

Wayworn Lovers Course of Action

Course of Action